There’s a peculiar kind of optimism in hash function development. Every few years, someone announces they’ve made hashing 20% faster, and everyone updates their dependencies, and then someone else announces they’ve made it 20% faster again. The speed of light hasn’t changed, but apparently the speed of XOR has.

Rapidhash is one of these incremental miracles. Derived from wyhash, it’s now used in Chromium, Meta’s Folly, Ninja, and Julia. It passes all of SMHasher3’s quality tests while being genuinely, measurably fast.

The C++ implementation is only a few hundred lines, but those lines are dense with choices. As the maintainer of the rapidhash rust crate, I thought I’d walk you through them.

The core operation

At the heart of rapidhash is the folded multiply, which we’ve covered in a previous article. Multiply two 64-bit numbers to get a 128-bit result, then XOR the upper and lower halves together:

RAPIDHASH_INLINE_CONSTEXPR void rapid_mum(uint64_t *A, uint64_t *B) RAPIDHASH_NOEXCEPT {

// multiply two 64-bit numbers to get a 128-bit result

__uint128_t r = *A; r *= *B;

// set A and B to the upper and lower halves

*A = (uint64_t)r;

*B = (uint64_t)(r>>64);

}

RAPIDHASH_INLINE_CONSTEXPR uint64_t rapid_mix(uint64_t A, uint64_t B) RAPIDHASH_NOEXCEPT {

rapid_mum(&A, &B);

return A ^ B;

}Every output bit depends on nearly every input bit from both operands. You get near-complete diffusion in a single operation. Modern CPUs have dedicated instructions for this (mulx on x86), so the operation that provides the best bit mixing also happens to be fast.

The secrets

Throughout the code, you’ll see references to secret[0] through secret[7]. These are eight magic constants:

RAPIDHASH_CONSTEXPR uint64_t rapid_secret[8] = {

0x2d358dccaa6c78a5ull,

0x8bb84b93962eacc9ull,

0x4b33a62ed433d4a3ull,

0x4d5a2da51de1aa47ull,

0xa0761d6478bd642full,

0xe7037ed1a0b428dbull,

0x90ed1765281c388cull,

0xaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaull

};The first seven are essentially random, though we prefer odd numbers with roughly half their bits set. The eighth (0xaaa...) is special: its repeating bit pattern can be represented in a single instruction on x86-64 and AArch64, whereas the others require a full 64-bit load. It’s only used once, in the final avalanche step.

Why static constants instead of deriving them from the seed? Speed. Loading constants is cheap; computing them isn’t. The downside is that static secrets expose seed-independent collisions, which we cover in a later article.

Small inputs: overlapping tricks

Small inputs are where hash functions spend most of their time. Most hash table keys are short strings, small integers, compact structs. If your hash function screams through 10KB inputs but trudges through 10-byte inputs, you’ve optimised for the wrong case.

Rapidhash has a dedicated path for inputs of 16 bytes or fewer:

if (_likely_(len <= 16)) {

if (len >= 4) {

seed ^= len;

if (len >= 8) {

const uint8_t* plast = p + len - 8;

a = rapid_read64(p);

b = rapid_read64(plast);

} else {

const uint8_t* plast = p + len - 4;

a = rapid_read32(p);

b = rapid_read32(plast);

}

} else if (len > 0) {

a = (((uint64_t)p[0]) << 45) | p[len - 1];

b = p[len >> 1];

} else {

a = b = 0;

}

} else {

// longer input handling ...

}The trick is overlapping reads. A 12-byte input reads bytes 0-7 and bytes 4-11 – two loads that overlap in the middle, capturing everything. A 10-byte input reads bytes 0-7 and 2-9. Whatever the exact length, you always do exactly two memory operations. Why << 45? Why this particular nesting order?

I wish there was good reasoning beyond “it works.” These patterns are largely empirical. There’s nothing theoretically optimal about p[0] << 45. It’s what emerged from trial and error, testing what’s fast while still producing a high-quality hash that passes SMHasher3’s statistical tests.

Care is taken to ensure the small path is wrapped in a _likely_ intrinsic, which tells the compiler to optimise this branch. The cost of a jump – or worse, a branch predictor miss – matters a lot when you’re only intending to hash 8 bytes with a handful of instructions.

This is a recurring theme in hash function design: small inputs get disproportionate attention. A 10-cycle overhead on an 8-byte hash that takes 20 cycles total is a 50% penalty. The same 10-cycle overhead on a 10KB hash that takes 5000 cycles is rounding error. Large inputs are already doing enough work that fixed costs disappear into the noise. Small inputs have nowhere to hide. So hash functions will happily add a branch or two to the large-input path if it shaves a cycle off the small-input path.

Medium inputs: the tail cascade

What about inputs between 17 and 112 bytes? Too big for the small-input path, too small to justify the full parallel machinery we’ll see later.

One option: a loop that processes 16 bytes at a time until you’re done. But loops have overhead. Counter updates, branches back to the top. For small amounts of work, the overhead can dominate.

Rapidhash simply manually unrolls the loop:

if (i > 16) {

seed = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p) ^ secret[2], rapid_read64(p + 8) ^ seed);

if (i > 32) {

seed = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 16) ^ secret[2], rapid_read64(p + 24) ^ seed);

if (i > 48) {

seed = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 32) ^ secret[1], rapid_read64(p + 40) ^ seed);

if (i > 64) {

seed = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 48) ^ secret[1], rapid_read64(p + 56) ^ seed);

if (i > 80) {

seed = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 64) ^ secret[2], rapid_read64(p + 72) ^ seed);

if (i > 96) {

seed = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 80) ^ secret[1], rapid_read64(p + 88) ^ seed);

}

}

}

}

}

}That’s six levels of nested ifs, each level handling exactly 16 more bytes. Is this better than a loop? For CPUs, yes. There’s no loop overhead. The branches are highly predictable – for any given input size, you take the same branches every time. CPUs love predictable branches; they can speculatively execute ahead without penalty and the code stays fairly compact.

Large inputs: seven parallel lanes

For inputs over 112 bytes, rapidhash switches to a parallel approach. Instead of one accumulator that each block feeds into, it maintains seven:

if (i > 112) {

// This multi-lane set up costs instructions

uint64_t see1 = seed, see2 = seed, see3 = seed;

uint64_t see4 = seed, see5 = seed, see6 = seed;

do {

seed = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p) ^ secret[0], rapid_read64(p + 8) ^ seed);

see1 = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 16) ^ secret[1], rapid_read64(p + 24) ^ see1);

see2 = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 32) ^ secret[2], rapid_read64(p + 40) ^ see2);

see3 = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 48) ^ secret[3], rapid_read64(p + 56) ^ see3);

see4 = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 64) ^ secret[4], rapid_read64(p + 72) ^ see4);

see5 = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 80) ^ secret[5], rapid_read64(p + 88) ^ see5);

see6 = rapid_mix(rapid_read64(p + 96) ^ secret[6], rapid_read64(p + 104) ^ see6);

p += 112;

i -= 112;

} while (i > 112);

// Combine all lanes

seed ^= see1;

see2 ^= see3;

see4 ^= see5;

seed ^= see6;

see2 ^= see4;

seed ^= see2;

}Why the complexity? Why not just process 16 bytes at a time in a simple loop?

The latency trap

Multiply instructions have latency and throughput, and these are different things. Latency is how many cycles until the result is ready. Throughput is how often you can start a new operation. On modern x86 processors, the multiply instruction has a latency of about 3 cycles but a throughput of 1 cycle. The CPU can start a new multiply every cycle, but each individual multiply takes 3 cycles to produce its result.

This distinction matters because of data dependencies. If you write:

result = mix(mix(mix(data, secret), secret), secret);Each mix needs the previous one’s output. The CPU can’t start the second multiply until the first one finishes. You’re stuck waiting:

Cycle 1: Start multiply A

Cycle 2: (waiting for A...)

Cycle 3: (waiting for A...)

Cycle 4: A ready, start multiply B using A's result

Cycle 5: (waiting for B...)

...You’re using 33% of your theoretical throughput. The CPU is perfectly capable of doing more work. You’re just not giving it any.

Modern CPUs are superscalar: they have multiple execution units that can work simultaneously. Your processor might have several ALUs for integer operations, separate units for multiplication, dedicated load/store units for memory access. In a single cycle, the CPU can be loading bytes from memory, XORing values together, and running a multiply - all at once, as long as they don’t depend on each other’s results.

The seven parallel lanes exploit this. Lane 0 feeds into seed, lane 1 feeds into see1, lane 2 feeds into see2. None of them depend on each other. The CPU can issue all seven multiplies in rapid succession without waiting for any results. Meanwhile, the XORs and memory loads for the next iteration can overlap with the multiplies from this one. By the time the first multiply’s result is ready, the CPU has already started plenty of other work.

Why seven specifically? It’s empirical. Enough lanes to keep the pipeline full, but not so many that you’re spending all your time on setup and teardown. Different CPUs might prefer different numbers. Seven seems to work well across a range of hardware.

Each lane XORs with a different secret (secret[0] through secret[6]). This prevents a subtle bug: if all lanes used the same secret and are then combined via XOR, an attacker could swap the data between lanes and cause hash collisions (5040 of them). With different secrets, the lanes diverge even when processing similar data.

Scrambling the seed

Before processing any data, rapidhash does something that seems almost paranoid:

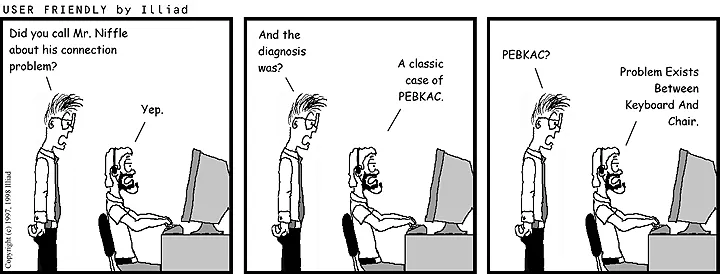

seed ^= rapid_mix(seed ^ secret[2], secret[1]);Why scramble the seed before you’ve even looked at the input? PEBKAC.

If someone passes zero as a seed (which they will, because zero is the default for everything), you don’t want your internal state to literally be zero. The internal state should diverge immediately from the seed, but a zero seed could cause some partial zero-collapse on the first few bytes of input.

However, this premixing is an unnecessary operation at the start of the hash function. Unless the compiler manages to optimise away this extra folded multiply step (when the seed is known at compile time), this seed scrambling will happen on every hash input. This isn’t captured on benchmarks because they all use constant seeds, but the rust implementation opts to instead utilise a RapidSecrets struct that lets a user reuse precomputed seed and secrets.

The final avalanche

After processing all the data, rapidhash needs to ensure the output satisfies the avalanche criterion: flip any input bit, and roughly half the output bits should flip. Short inputs and the remainder bytes of longer inputs won’t have been processed yet, and so our final mixing step looks like:

if (i <= 16) {

// set a and b

} else {

// ...

// on long inputs mix the final 16 bytes of the input data

// p is the input pointer; i is the input length

a = rapid_read64(p + i - 16) ^ i; // Length XORed here

b = rapid_read64(p + i - 8);

}

// combine the lanes and seed with a folded multiply

a ^= secret[1];

b ^= seed;

rapid_mum(&a, &b);

// a final avalanching step with another folded multiply

return rapid_mix(a ^ secret[7], b ^ secret[1] ^ i);Two rounds of mixing (rapid_mum then rapid_mix) ensure every bit of the final output depends on every bit of the input. The length gets XORed in, so "abc" and "abc\0" produce wildly different outputs rather than related ones.

The constant secret[7] (0xaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa) only appears in this final step for avalanching. Its repeating bit pattern can be represented in a single instruction on x86-64 and AArch64 architectures, whereas the other secrets require a full 64-bit load.

What’s next

None of these techniques are unique to rapidhash. Overlapping reads, unrolled loops, parallel lanes, final avalanche steps – you’ll find variations in xxHash, wyhash, and half a dozen others. The interesting question isn’t “what does rapidhash do?” but “why does this particular combination benchmark well on this particular hardware in this particular year?”

Hash function development is part science, part archaeology, part throwing things at a wall. The theory tells you what properties to aim for; the benchmarks tell you if you got there; the gap between them is filled with trial and error.

The next article covers porting rapidhash to Rust, where the Hasher trait has opinions about how hash functions should receive their input. Spoiler: those opinions don’t align well with block-based hashers like this one. And there were many months of frustrating trial and error.